Ever since starting Blossom, our mission has been clear: we want people to fall in love with speciality coffee and encourage them to be part of a movement that helps to protect it for future generations.

While we enjoy the incredible luxury of speciality coffee on a daily basis, the farmers responsible for producing these lots too often do not receive the necessary income to ensure financial stability for their businesses. In these instances, often the best case scenario is that farmers will start to cut corners on sustainable and quality-focused production, while in the worst case scenarios they will be driven out of the industry altogether and into more profitable crops.

Why Transparency?

We feel a responsibility to work in a way which ensures financial stability for the producers with whom we work, as it is only by increasing sustainability throughout the value chain that we believe speciality coffee production can be secured. We see transparency as absolutely central to this.

By publishing our data and openly communicating how much is being paid for our coffees, we hope to be part of a movement which normalises prioritising living incomes for producers and increases awareness for consumers, while in doing so distinguishing ourselves from those that use ‘transparency’ only as a marketing tool.

The Pledge

The idea to create The Pledge was developed during the transparent trade colloquium in Hamburg in 2018. As a group of likeminded professionals in the coffee supply chain, signatories of The Pledge feel that transparency should necessarily mean one thing: transparency of pricing in coffee negotiations.

“Companies that sign The Pledge agree to share a fixed set of variables when reporting on green coffee purchases. Together, we aim to create a common standard for transparency reporting that is applicable throughout the coffee world. By disclosing additional information like the name of the producer organisation, the lot size and the cup quality of the coffee, we add context to our transparency reports that makes them comparable and truly transparent.”

To sign The Pledge, a minimum of one coffee that we have bought must be considered transparent according to the agreed criteria. However, we are proud to be publishing data for 100% of coffees bought in 2021.

Read our 2021 Transparency Report here.

FOB Pricing

Free on Board (FOB) is the price of the coffee packed and stacked in a container ready for shipping. The FOB price includes the total paid to the farmer plus domestic transportation, milling, sampling, packing, and so on. The reason why we use FOB data specifically is simply that this is the most common way of communicating price globally, and is the agreed way of communicating prices in The Pledge. While this is not a perfect indication of how much is paid to the farmer, we believe that by working with transparent supply chains and the same importers and producers year on year, we can be confident that the producers are receiving the majority of the FOB price and that there is an upward trend over time. Please note that all FOB prices published are those negotiated between importer and producer/exporter, and we’re grateful to each of them for sharing this data.

The FOB price does not include the cost of shipping to the UK, financing, storage, the importer’s margin, transportation to our roastery and finally roasting (which results in a 15% weight loss), all of which are accounted for before adding our own margins.

Ever since starting Blossom, our mission has been clear: we want people to fall in love with speciality coffee and encourage them to be part of a movement that helps to protect it for future generations.

While we enjoy the incredible luxury of speciality coffee on a daily basis, the farmers responsible for producing these lots too often do not receive the necessary income to ensure financial stability for their businesses. In these instances, often the best case scenario is that farmers will start to cut corners on sustainable production, while in the worst case scenarios they will be driven out of the industry altogether and into more profitable crops.

We feel a responsibility first and foremost to work in a way which ensures financial stability for the producers with whom we work, and we see transparency as absolutely central to this. By publishing transparency data and openly communicating how much is being paid for our coffees, we hope to challenge the current pricing mechanisms based on commodity markets and to distinguish ourselves from those that use ‘transparency’ only as a marketing tool.

At the end of 2021, our first full year in business, we’ll be publishing our first transparency report. In the mean time, we are sharing the importer, FOB* price, volume purchased and purchase history for every coffee we buy on the shop pages of our website. As a very small-scale coffee roastery, we work with a handful of importers to source our coffees rather than engaging in ‘direct trade’. We strictly only work with those who share our vision of securing a sustainable future for coffee producers, and who are open and supportive in sharing transparency data. Please note that all FOB prices published are those negotiated between importer and producer/exporter, and we’re grateful to each of them for sharing this data.

*FOB: Free on Board is the price of the coffee packed and stacked in a container ready for shipping. The FOB price includes the total paid to the farmer plus domestic transportation, milling, sampling, packing, and so on. While this is not a perfect indication of how much is paid to the farmer, we believe that by working with transparent supply chains and the same importers and producers year on year, we can be confident that the producers are receiving the majority of the FOB price and that there is an upward trend over time.

To delve a little deeper into the subject, we spoke to Andrew Tucker from Volcafe who has been instrumental in helping us to source our El Salvador coffees, and to whom we couldn’t be more grateful for his openness and transparency.

What is the impact of low prices on the speciality coffee industry?

Whilst many would like to believe that specialty prices are not influenced by the commodity exchange prices the fact is that producers will sell their coffee at the going rate of the market +/- the differential premium that relates to their specific origin/quality. So the commercial market still acts as the benchmark for most specialty transactions, albeit at arm’s length.

So whilst a true roaster > producer transaction may be negotiated purely on quality, irrespective of the wider market pricing, the reality is that most specialty coffee is still sold with a degree of relativity to the NY ‘C’ because that market price determines the differentials paid for qualities over and above the market.

In terms of the impact of low pricing, it often means that roasters and retailers reap much of the benefit in terms of the margins available along the supply chain, whilst producers lose out from a low-price market environment.

One begins to see that really the vast majority of price risk therefore falls at the producers door, and that is probably the single biggest discussion point facing the specialty industry: how can we all work together to alleviate more of that price risk from the producers and spread it more evenly amongst all of the actors. Really the answer lies with the consumers, and the need for them to pay more for their cup. But it also requires a shared and transparent relationship all the way back to origin because for the market to work efficiently and profitably for all concerned, each actor’s business needs to be economically sustainable.

Obviously sustained periods of low pricing means unsustainable livelihoods for producers hence why so many farmers have ditched coffee either in favour of more profitable crops, or indeed for alternative professions and incomes all together, and that is an ongoing, very real issue in most producing countries.

In the context of green coffee buying, to what extent do you think transparency is valuable?

With reference to above, I think it’s vital. The need for transparency is driven by the need for all actors in the supply chain to be able to sustain or even grow/improve their businesses, incomes and livelihoods.

So an open and transparent relationship between all, understanding what each party needs from the relationship to make it not just viable but prosperous is critical in my opinion. The more we understand about each of our partners businesses the better we can address the issues at hand. So for me that starts with Cafes/Café owners understanding the margins and cost of doing business by their roasting partners in order for them to maintain buying green coffee at sustainable prices, which are in turn passed on by the importers to the exporters and on to the producers.

If you’re a café demanding cheap kilo prices, free machinery and lots of free training from your roaster then it’s not hard to work out that the prices afforded by that roaster for green coffee are going to be low. Meaning less money ultimately going back to the importers, the exporters and ultimately, the producers. That is unsustainable and for me, a race to the bottom.

How can coffee farmers benefit from more transparent supply chains?

In my (somewhat limited) experience of dealing with farmers and buying from them directly, the more they can understand about the needs of the roaster as the primary buyer in the supply chain, the better they can at least try to ensure their own business can meet those needs in a more economically (and sometimes environmentally) sustainable way. That might involve labour planning, raw material procurement, investment planning or adopting new/varied agronomic practices for example.

Planning ahead is key, regular communication between all parties and a lot of mutual trust & respect will help to hopefully de-risk, nurture and protect sustainable supply chain relationships.

What are the limitations of FOB data?

I get asked this a lot, and whilst it’s great that there is an increasing quest, mainly from roasters about pricing transparency, FOB pricing only really paints a small part of the picture.

It’s only really relevant as a singular piece of data if you have a full understanding of the whole supply chain. It depends heavily on who is selling the coffee on a FOB basis: is it an exporter? Is it a co-operative or is it a vertically integrated producer? Therefore how does the FOB price relate to the price received by the producer (farmgate price).

Without that knowledge, it (the FOB price) is limited to only really telling a roaster for example how much margin the seller is making from the transaction.

In many cases I have seen, little or no questions get asked to really understand its relativity to domestic COP, how is coffee transacted in origin, what quality premiums exist for different grades, what are export costs and farmgate pricing, Not to mention socio-economic data such as cost of living and currency valuations.

Much of the tech finance being poured into the coffee industry currently is aimed at addressing this very issue to ensure verified transparent price data is obtainable by all. It’s a complex subject and is typically easier to dissect within the specialty market because supply chains can often be smaller and more transparent from producer to consumer.

As any coffee buyer will tell you, sourcing coffee involves planning far into the future. In our case, we started planning for our Colombian purchases the very same week we launched Blossom, back in June 2020.

We knew this coffee would play a central role in our offering, making up part of Blossom Espresso as well as being roasted separately for both our single origin espresso and filter menus, and with that in mind, we knew the kind of quality and sensory profile that we required. Most importantly, though, was finding a coffee which we could plan to buy every year, as part of our mission to develop long-term, mutually beneficial and fully transparent relationships with the people responsible for producing these beautiful coffees. Thankfully for us, Kyle of Osito Coffee had a specific group of producers in mind: Mártir, a group of 18 producers from La Plata, founded and lead by Didier Javier Pajoy Ico.

In the words of Kyle: “With Mártir, we pay the producers directly and Didier earns nothing extra for volume. He essentially volunteers as the leader whose only motivation is to create a sustainable supply chain for himself and his associates. There are no additional volume-driven incentives so the money he makes as well as the rest of the producers is rooted in quality first and second, the volume that each of them can produce for themselves.

They are bound by a passion for environmentally conscious farming and for the results it yields in the cup. Almost all of the producers are farming organically or are in transition to organic practices. Didier has also spent a significant amount of time teaching producers how to make organic fertilisers and also how to best deal with waste water from washing coffee.

The goal for Mártir is always to produce the highest quality coffee in a manner with the lowest impact on the environment.”

Six months and many phone calls and sample tastings later, the coffee arrived with us here in the UK, tasting delicious and ready for us to share with you. We recently spoke to Didier, to find out a little more about the group.

Could you give us a little background information about how and why the ground was formed?

“When I first started as a producer, the price of coffee made it unfeasible. Therefore, I decided to study the world of coffee. Firstly, I studied production followed by sensory analysis and barista skills. This way, I changed the farm’s focus and started producing speciality coffee with my brothers. This yielded better financial outcomes. Secondly, I also wanted to work on the social aspects of the business. In collaboration with other producers we created a group called Crecert. However, I left after my goals weren’t accomplished and created Mártir Coffee (comprised of 18 families located across four districts in the municipality of La Plata, Huila.)”

As a group, what are your main goals?

“We strive to organise ourselves, seek commercial partnerships and aim to obtain extra value on our coffee. Also, given the individual farms are small, we must work as a team to increase our volume of production. (Our goal is) to produce high quality coffee and to put our name out there together.”

And what are your biggest challenges?

“Difficulty getting pickers, lack of infrastructure at wet mills and producers’ lack of knowledge in relation to customers demands for certain flavour profiles.”

The name Mártir is interesting, translating to martyr. Where does the name come from?

“Mártir is named after a catholic priest, Pedro Maria Romero, from the municipality of La Plata, Huila (killed during the outbreak of the Colombian civil war known as La Violencia).”

What are your plans for the future?

“Colombia faces high unemployment. My plan is to encourage young people to overcome this by coming together to produce high quality coffee as a means to obtaining a life project.”

You can pick up a bag of Mártir over on our webshop here.

Special thanks to Manu Rico for his assistance in the translation of the interview.

We have recently launched our Competition Series here at Blossom with the stunning Finca Villarazo, an incredibly complex and tropical coffee grown by Jairo Arcila in the Quindio region of Colombia. To delve a little bit deeper into this coffee we had the pleasure of sitting down with Jairo’s son, Felipe, to find out a little more about the complex processing methods used at his father’s farm and what some of the ambitions are for the farm and their distribution company, Cofinet.

Could you give us a little background information on Cofinet?

I started Cofinet five years ago in Australia with my brother with the idea of helping our family sell their coffee for a better price, as they’d been struggling with low prices due to the low C market for 15 years. As a family we have been involved in the business of growing and distributing coffee in Colombia for over 4 generations, but it was in 2015 we expanded our operations and began exporting speciality coffee to the rest of world.

We realised every year that we could help more and more growers by connecting good roasters with them, so the business continued to grow for three and half years in Australia. At this point we decided to start selling into other countries slowly, without losing our focus of paying higher prices to farmers and being able to provide high quality to roasters as well. We currently work in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Singapore and now the US, representing and supporting a large number of speciality coffee growers and creating sustainable, ethical and long-term relationships.

It’s clear looking at your offerings that experimental processing is what seems to set you apart from other importers. What do you find appealing about encouraging farmers to use experimental processing?

In the first three years we did a lot of work with washed processing, but in Colombia there’s a lot of very, very, very good washed coffees so in order for coffee to be something ‘out of the box’, it had to be something else: either a long fermentation, a honey or a natural. Roasters around the world are spoiled with very good washed Colombian coffees and ultimately if there is too much of this same style and quality, then the price goes down. The experimental processing has a very strong impact on the cup profile, and we found that roasters have been really appreciating this.

You describe the coffee we have selected from Finca Villarazo as ‘EF2’ (Experimental Fermentation 2). Could you outline what this is?

EF2 came after a few years of trial and error at our farm, and we’re now encouraging farmers in every part of Colombia to use it as it works really well and is also very easy to do. It involves floating and hand sorting every single batch that is picked before storing the cherry in GrainPro bags for 48 hours. At this time the cherries are in an anaerobic environment and the temperature is regulated by the Co2 produced naturally, so we get a cold environment in which we can get delicate, fruity notes and avoid overly wild flavours.

We’re proud to be roasting coffee produced by your father, Jairo. Could you tell us about his background in coffee and about how receptive he was to these new processing techniques?

Oh man! He was very reluctant to it and still is. My dad has been working in the coffee industry for 41 years, previously for the second largest exporter in Colombia, so he’s very, very old-school. For him, the cheapest he could dry, process and deliver his coffee was the best option because he was only paid by volume. Regardless of how clean his processing was or how well stored his coffee was, he was only paid by volume, so it’s been very tricky to work around this mindset.

At the beginning when he saw me separating small lots from different growers and processing naturals by myself, he told me I was crazy and not to waste time. It’s always hard to change your father’s mindset, which I think is something everyone has to deal with in their lives. The only way that I’ve managed to change my dad’s mind is by giving him roasted coffee from our customers, and there’s nothing that makes his more happy.

Finca Villarazo is available to pre-order here.

You can learn more about Cofinet here.

Taking an approach that is responsible towards people and the planet is central to everything we do at Blossom. Whilst much of this work takes place across the coffee supply chain we are also committed to taking a leading role in supporting initiatives closer to home, building a healthier and more sustainable version of the city we love, work and live in.

One of the ways we do this is through our work with Manchester City of trees, a local charity who aim to re-invigorate the city’s landscape by transforming underused, unloved woodland and planting a tree for every man, woman and child who lives there, within the next 30 years.

With an ever-increasing number of us choosing to live in urban areas, our dependency on trees and green spaces within our cities for physical and mental wellbeing has never been greater. Urban trees and woodlands also help to lock up carbon, filter air pollution, reduce flood risk and provide essential habitats for wildlife. They are nature’s ace card.

How do we help?

For every retail bag of our Blossom Espresso we sell we donate a percentage of the profits to City of Trees (£1 per kilo). That means, with your help, every 40 bags of coffee we sell will fund the planting of a new tree here in the city.

We also work with City of Trees on regular competition giveaways, most recently donating the funds to support the planting of 12 trees here in the city alongside a years free coffee subscription to one lucky winner.

More information on City of Trees

City of Trees is the Greater Manchester part of the Northern Forest, an ambitious project to plant 50 million new trees across the North of England around the cities of Liverpool, Chester, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield and Hull.

City of Trees projects are focussed around;

Planting trees, creating and managing woodlands – We work with landowners and volunteers to plant trees, create new woodlands and bring unused or unloved woodland back to life

Urban orchards – We plant fruit trees and train local people to look after them, so more communities can get outside and spend time together

School projects – We plant trees in schools, create outdoor classrooms as well as engage children to strengthen their relationship with trees, woods and wildlife

GreenStreets – We turn gloomy streets into gorgeous green backdrops by planting street trees in the urban environment

To date, Manchester City of Trees have planted over 537,000 trees.

You can find more information about City of Trees and how to get involved here.

There is a lot of talk in our industry about the sustainability of coffee supply chains. You’ve probably heard one roastery or another describe their relationships with coffee producers as direct or transparent, but often what these words are used to describe can vary greatly depending on who you ask.

So what are we really talking about when it comes to buying coffee sustainably, and how can we as an industry do better? We got in touch with one of the most knowledgeable coffee buyers we know, Kyle Bellinger of Osito Coffee, to find out more.

Can you tell us a little about Osito and the mission you are on?

Osito was founded in early 2018 by Jose Jadir Losada and myself, Kyle Bellinger. We wanted to facilitate relationships between coffee farmers and roasters. What that meant for us was establishing an exporting firm in Colombia and an importing company based in the US. Our goal is rather simple; to change the way green coffee has traditionally been bought and sold and shift the focus to building and maintaining longstanding relationships.

What are ‘direct relationships’ in coffee buying and why are they important?

Unfortunately, the term “Direct” has become somewhat abused. The notion behind it is something admirable but given that it is not regulated, some small roasters can take a screenshot of a farmer off their importer’s Instagram account, buy their coffee and call it “Direct Trade.” On the flip side of that, I have approached many roasters who have said they can’t work with us because they buy “direct.” Ok, so yes, they have a relationship with a farmer but in almost all cases, you still need an exporter and an importer (of which, we are both) to help facilitate relationships.

Moreover, in almost every one of these scenarios, it’s a small roaster who has a relationship with a wealthy, hyper-connected farmer who has access to the luxuries of the modern world (internet, cell phone, etc) and is usually only selling them minuscule quantities of fancy “toy” coffee. Sadly, this is not the case for many small farmers and when roasters give me that boilerplate answer, it indicates to me that they don’t understand the real needs of the industry and that they are intentionally passing up opportunities to work with people who are in desperate need of a relationship. It’s a lot more catchy for a small roasting company to say they work with “Fancy Coffee Estate X” and their “Triple Cold-Fermented Green Tip Gesha” as opposed to “Farmer Association Y” who produces the vast majority of the 84/85 point Castillo and Var. Colombia that the same roaster gobbles up en masse and for which they want to pay as little as possible. This is obviously anecdotal and a generalisation but I think it’s important for roasters to consider the quality of the relationship they are referring to as “direct.”

Lastly, I’ll say that as a farm owner myself, I greatly appreciate clients who are committed to buy even though we have never met face to face and even though they have never visited the farm. It’s the commitment that is the key element. It doesn’t matter to me if someone buys our coffee once, visits our farm and takes a selfie so they can call it “direct.’ So I guess what I am getting at is that “direct” doesn’t matter as much as the real commitment behind why people feel the need to go “direct.”

What is ‘fixed pricing’ and why is it important?

It’s about stabilising prices for farmers. Even in-country buyers of specialty coffee, more often than not, tack their prices and premiums to the fluctuating C Market. Instead, we try first, to buy as much as we can from each of our producer partners. This means that we operate on multigrade contracts, buying not just the high-scoring lots but the somewhat underwhelming and unexciting lots as well. Secondly, we fix prices across all qualities in advance so producers know that it’s not going to change. In my opinion, fixing prices is the best way for farmers to get out of their usual starvation incomes offered by the rest of the industry.

In what ways are most supply chains in coffee currently unsustainable?

That’s a complicated question with no one succinct answer but ultimately it comes down to price and volatility. Farmers in Colombia and in many other parts of the world are subjected to volatile internal markets tacked to the C Market on the NYSE. Prices fluctuate daily so there is some volatility but if you look at historical coffee prices, they are mostly quite low, floating between $1 and $1.50 USD/lb for the last 40 years.

Prices are more or less dictated by the crop yield in Brazil (the world’s largest exporter of coffee) and the prices that the big buyers (Nestle and the like) are willing to pay, and it isn’t very much, especially when you factor in inflation. At the same time, farmers costs have more or less risen in lockstep with inflation.

This isn’t comprehensive though. There are many issues in the coffee industry that make most supply chains unsustainable. Environmental and social concerns are also quite pertinent, though I suspect that many of those wrongs could be righted through simply paying more for coffee.

What steps should be taken in order to achieve sustainable supply chains?

I think that depends who you are asking. If the question is directed at me as an exporter/importer, I would say that my colleagues and I should be willing to roll up our sleeves and, figuratively speaking, get our hands dirty when it comes to building and maintaining relationships with farmers. Being on the ground and in person with farmers does help create a bond that makes me a much better advocate for relieving their plight.

If the same question is directed more at a roasting company, I would say the same with the added footnote that specialty coffee roasters should be on the front lines telling consumers that they shouldn’t be comfortable paying what they have always paid for coffee. Roasters assume they are bound by what they perceive the market will pay and often get complacent. Farmers need them to push harder and help raise the price floor.

Lastly, if the question were directed at a consumer. It’s pretty simple: know who you buy from and why. Don’t look for a deal. Coffee is a luxury product that we have commodified. Don’t forget that while it’s a luxury for you, it’s a farmer’s way to feed his/her family.

Finally, in what ways do you envisage that small-scale coffee farmers will be impacted by the economic effects of Covid-19?

I think it’s still a little early to say. Early on, the market surged as traders scrambled to buy coffee in anticipation of a slow down at the ports. Since then, in a place like Colombia, where the local market is tied directly to the USD-based C Market, the weakening of the Colombian peso since early March has translated into higher than average prices. These things have all been good for the average farmer.

At the same time, many of our competitors defaulted on contracts worth millions and millions of dollars. In most cases, it’s the farmer who loses money when a buyer defaults.

While coffee consumption is steady, I think the specialty market will slump as people change HOW they consume coffee and small to medium-sized specialty roasters who are already strained by their shops and wholesale accounts being closed, will be slow to react and miss out on business that will then go to the big boys who are buying cheap commodity and low-specialty coffee at unsustainable prices.

Time will tell. If the world begins to open up in the next few months, some downside will be mitigated but it’s hard to tell how long it will be before people can really go back to coffee shops.

With many of our favourite coffee shops forced to keep their doors closed over the last few months, the amount of coffee being consumed in our homes has skyrocketed. Whether you’re a full V60 convert with a temperature controlled kettle or just brewing up in a cafetière, the most common question we often get asked is same: what is the best way to keep our coffee fresh and tasting it’s best?

The concept of freezing coffee beans has been floating around the industry for several years but it wasn’t until recently that the benefits of freezing at home have started to be explored in a little more depth. To find out more we chatted with Tom Finch, co-founder of Manchester Coffee Archive, and a leading expert on home coffee freezing.

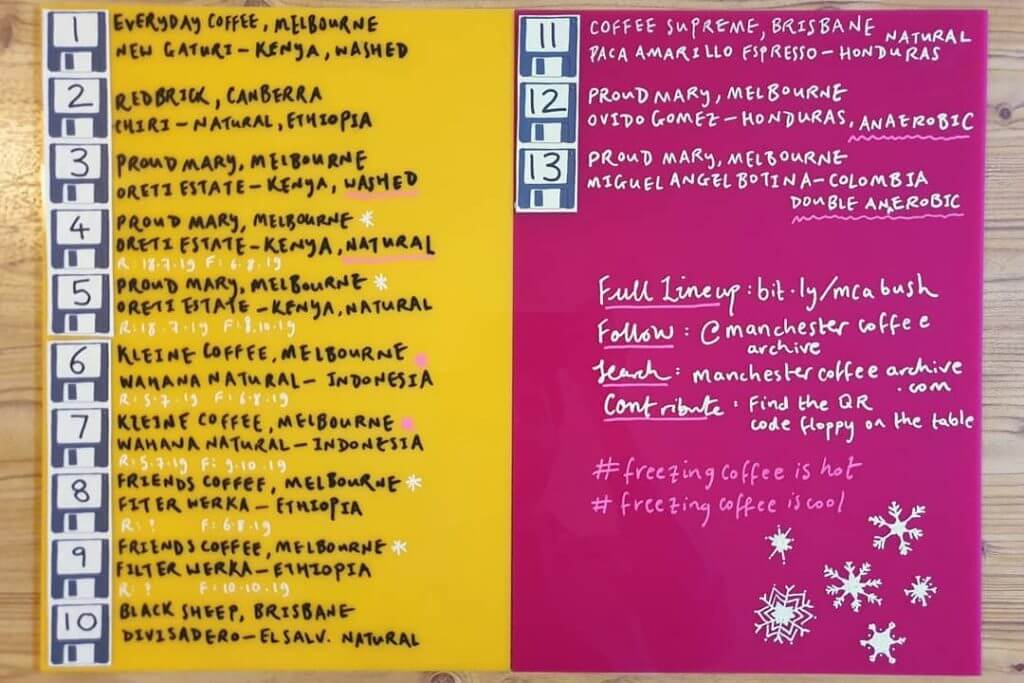

What is Manchester Coffee Archive and what do you guys do?

Manchester Coffee Archive is a crowd-sourced collection of coffee beans, stored in freezers to preserve their flavours for a long time. We freeze coffee so we can put together themed tasting lineups, for anyone who wants to come and taste some nice coffees and meet fellow enthusiasts. We rely on coffee contributions to keep the Archive going, which currently holds over 400 different coffees.

So, what are the benefits of freezing coffee?

Freezing allows you to massively extend shelf life, which is how we are able to put something as ridiculous as MCA together. We have coffees in the freezer that are over two years old, they’re still tasting fresh and we expect that they will remain stable for some time before any noticeable degradation in taste occurs. It also means we can keep a variety of coffees in stock and not have to worry about running out. There are some interesting benefits to grinding frozen coffee for espresso, mainly to do with grind consistency and particle size distribution – we haven’t investigated this ourselves but coffee-freezing evangelists Michael Cameron (of St Ali in Australia) and Christopher Hendon (notable coffee scientist) have done interesting research on this subject, which I’ve highlighted in What We Know About Freezing Coffee (linked on our Instagram bio and website).

Will I need lots of expensive equipment? Do I need a vacuum sealer?

Vacuum sealing in plastic is the current “gold standard” in the coffee freezing world, but it is possible to get into freezing without purchasing a vac sealer. When packaging coffee to put in the freezer the aim is to both remove as much oxygen as possible from the packaging and also to keep the damp freezer air out of the packaging. Vac sealers do a great job on both of these, but I have heard anecdotally of people just throwing a retail bag in the freezer and it tasting great many months later. Lots of people use repurposed jars or even a humble ziplock bag. We have begun to investigate this more, we’ve done some experiments and have some experiments lined up to try and figure it out, but for now I would say just seal it up as best you can. However, if you want to really get into it and freeze coffee for a year or more a vacuum sealer is the way to go.

Can I just use my freezer at home?

Yes, most home freezers run at -20C which is fine to preserve coffee for at least a couple of years. We use two small domestic freezers at MCA, which will be fine until the walk-in bunker facility is complete.

Is there an optimum time after roast to freeze coffee?

Freezing essentially stops the clock, so whenever it tastes best is a good time to freeze. At MCA we aim for 10 days past roast, which is good for cupping, filter brewing or espresso, giving us a bit of wiggle room for when we come to use our little coffee samples.

What does freezing do to the beans? Do they taste different? Or taste better?

Here’s the thing, due to the extremely low water content of roasted coffee, it doesn’t really freeze at all. We call it freezing because… it is in the freezer. But, really, it is just super-chilled to slow down all the biological processes that are happening in the beans. In our experience coffee from the freezer tastes the same as it did before it went in. The only way frozen coffee tastes better is that you don’t ever end up brewing stale coffee!

Do you need to let the beans defrost or can you grind from frozen?

You can use beans straight from the freezer in the same way as if they were at room temperature, although you might need to adjust your grinder to a slightly finer grind setting. It is best to just try the same grind settings you would normally use first and take it from there. At home I often freeze a couple hundred grams at a time. When I take a bag out of the freezer, if I only want a cup or two of that particular coffee, I weigh out what I want then reseal and put the bag back in the freezer. If I decide that I want to drink that coffee for the next few days in a row, I just keep the bag out and let it come to room temperature over time. This “unpauses” the clock on ageing, but since I froze the coffee fresh, it doesn’t matter.

Can you keep refreezing the same bag of coffee or only do it once?

Re-freezing seems fine for coffee beans, we did a very small-scale experiment a while ago where we blind tasted coffee re-frozen multiple times vs. coffee that had been frozen once and there didn’t seem to be a noticeable difference. My favourite soundbite on this is from Michael Cameron: “this ain’t chicken, you can re-freeze!”.

Are there any biodegradable vacuum sealing plastic pouches on the market?

There are, but the ones we have come across so far aren’t suitable for most domestic vacuum sealers like the one we use at MCA. Freezer air is quite damp so you need to be careful using any material that will degrade in that kind of environment. Vacuum sealing plastic can be reused to some extent, but unfortunately recycling options for this type of plastic are very inaccessible in the UK. I would point out that by freezing in plastic like we do, we are avoiding wasting coffee, an issue on which Umeko Motoyoshi has curated a great deal of information in Not Wasting Coffee. Creating one type of waste to avoid another is a trade-off we’re happy with for now, and we hope that more alternatives will be available in the future.

Manchester Coffee Archive tastings are currently on hold due to COVID-19 but they are planning to return when it is safe to do so.

To find out more and contribute to the archive you can find them here.

With the last couple of months still overwhelming and preoccupying the mind, it can be extremely tempting to turn a blind eye to the alarming stories being reported from coffee producing countries of the damaging impact climate change is already having on coffee production around the world.

Altered rainfall patterns, droughts, lower crop yields and increased numbers of pests and diseases are all pointing to fact that climate change is no longer something to prepare for in the future, we are entering a critical time right now, with very real and significant adverse effects in the short term.

We recently sat down with Hanna Neuschwander, Strategy & Communications Director for World Coffee Research, to learn a little more about the organisation that is on a mission to safeguard the future of coffee through collaborative scientific research and development.

For those new to WCR, can you tell us a little bit about the organisation and the mission you are on?

World Coffee Research was created by the global coffee industry in 2012 in recognition of the need to accelerate innovation in coffee agriculture. WCR enables coffee roasters and other coffee businesses to invest in precompetitive, advanced agricultural R&D to transform the coffee sector to be productive for industry, profitable for coffee farmers, and sustainable for the world. We work on a global, precompetitive basis. Currently, 210 companies large and small from around the world support this work.

Consumers are gradually starting to hear the term ‘Agricultural R&D’ being used more often in the coffee industry but could you give a description of what this term means?

The coffee we drink today (like much of the food we eat) is the result of research that happened in the past – breeders creating new varieties for farmers to grow, agronomy researchers figuring out the optimal amount of nutrition that coffee trees need, or disease researchers learning about the life cycles of key pests so that they can be better managed on the farm. The coffee that our children will drink will be the result of research we do today.

Research is an essential basis for improving the ‘goodness’ of coffee – how good it tastes, how good it is for the planet, and how good it is for people who grow it. Of particular concern right now is the economic sustainability of coffee farming – whether farmers can make a good living from coffee.

Agricultural R&D is a foundational contributor to the economic sustainability of coffee farming; farmers who have access to agricultural innovations like improved varieties are much more likely to be profitable from their farming.

What is the multi-location variety trail (MLVT)?

This is an unprecedented global trial testing the same 31 coffee varieties on 40 research stations in 22 countries. The purpose is twofold: To understand scientifically more about the nature of the genetics x environment interaction (i.e., how different varieties perform in different agro-ecological environments – as you can imagine, this is very relevant for climate change), as well as to give countries access to observe up close varieties that they previous have not had access to see.

In most countries, there are only a handful of varieties that farmers commonly grow, and most have been around for decades – this trial allows countries to observe many varieties at once that are new to them (even if they may be common in other areas of the world) to see if any are promising. If some varieties do very well, those countries might seek to commercialise the varieties for farmers in their countries. Working with existing varieties in this way is one way to bring innovation to farmers on a faster timescale than breeding (which, for a tree crop like coffee can take 15-25 years).

Can you tell us a little bit about DNA fingerprinting and why it is important?

In the past, to tell one variety apart from another, all you had to go on was what it looked like. This is tricky for coffee. Many arabica varieties look very similar to one another, and most farmers (and even many countries) don’t have detailed records about the varieties they have. DNA fingerprinting is a shortcut that allows you to identify the variety based on its genetics – kind of like how researchers right now are able to track different strains of Covid19 that have moved around the world.

It matters because different varieties do different things – but if you don’t know what variety you have, how can you be sure you have the right varieties for the conditions on your farm? How can you be sure you are giving the trees what they need? Not knowing their varieties exposes farmers to unnecessary risk, when they already bear so much of it. Can you imagine a vinyard not knowing what kind of grape they grow? Or a tomato farmer not knowing what varieties he has? And this is just at the farm level. What about at a nursery? Or even worse, a seed lot (which supply nurseries with their seed)? In most coffee producing countries around the world, there are not professionalized systems for checking or ensuring the genetic purity of the seeds they are producing and that eventually make it into farmers fields. Many, many, many seed lots and nurseries are sending out plants into farmers fields that are not genetically pure, that are mislabeled, that are the incorrect vareity.

We don’t hesitate to use the word ‘crisis’ to describe the state of most of these systems. Having cheap, rapid methods to test genetic purity can totally change that situation and help first seed lots, and then nurseries – and eventually individual farmers, and even roasters – be assured of what they have.

Can you provide an introduction as to what F1 hybrids are?

A new group of varieties created by crossing genetically distinct Ara-bica parents and using the first-generation offspring. There are only a handful of F1 hybrid coffee varieties in the world, all developed in the last 10 years, and only recently commercially available to farmers.

In coffee as in other crops, F1 hybrids have the potential to combine traits that matter most to farmers – higher yields and disease resistance – with the trait that matters most to consumers – taste, a combination that has been difficult to attain in the past. F1 hybrids are notable because they tend to have significantly higher production than non-hybrids. Early trials of coffee F1 hybrids showed 22-47% higher yields, without losses in cup quality or disease resistance. Recent results show they maybe also be more robust in other ways, such as tolerant to frosts.

Hybrids hold great promise to revolutionize the coffee industry through genetic progress, the way they did for maize in the last century. But F1 hybrids are limited by a key constraint: Currently, they can only be produced by technically sophisticated nurseries, of which there are only a handful in the world. Therefore, although these varieties are ‘best in class’, few farmers have access to them.

Another critical issue with F1s is that seeds taken from F1 hybrid plants will not have the same characteristics as the parent plants. This is called ‘segregation’. It means that the child plant will not look or behave the same as the parent. For smallholder farmers who are used to saving their own seed, this is a challenge to communicate, but it’s critical because using F1s will pose a significant risk to them if they save the seed. It is critical for farmers to know that F1 hybrids should only be purchased from trusted nurseries.

What is the ‘sensory lexicon for coffee’ tool? And what does it hope to achieve?

The goal of the World Coffee Research Sensory Lexicon is to use for the first time the tools and technologies of sensory science to understand and name coffee’s primary sensory qualities, and to create a replicable way of measuring those qualities.

Just like a dictionary reflects broad, expert agreement about the words that make up a given language, the lexicon contains the tastes, aromas, and textures that exist in coffee as determined by sensory experts and coffee industry leaders.

Despite the fact that we have many good tools for evaluating coffee, such as rigorous cupping protocols, none of them is suitable for scientific inquiry. There are three things about the lexicon that are fundamentally different from other sensory evaluation tools:

1. It is descriptive. The World Coffee Research Sensory Lexicon doesn’t have categories for “good” and “bad” attributes, nor does it allow for ranking coffee quality. It is purely a descriptive tool, which allows you to say with a high degree of confidence that a coffee tastes or smells like X, Y, or Z.

2. It is quantifiable. The World Coffee Research Sensory Lexicon allows us not only to say that, for example, a given coffee has blueberry in its flavour or aroma, but that it has blueberry at an intensity of on a 15-point scale. This allows us to compare differences among coffees with a significantly higher degree of precision.

3. It is replicable. When the World Coffee Research Sensory Lexicon is used properly by trained sensory professionals the same coffee evaluated by two different people – no matter where they are, what their prior taste experiences is, what culture they originate from, or any other difference among them – will achieve the same intensity score for each attribute. An evaluator in Texas will get “blueberry, flavour: 4” just the same as one in Bangalore.

These three factors allow us to ask and answer scientific questions, like how a given factor X (coffee variety, farm management practice, brewing method, etc.) impacts the flavour of a coffee. Controlling for as many factors other than the X factor as possible, we can submit the coffee samples for evaluation to a group of sensory scientists who have been trained in the use of the lexicon. They can assess the samples, and then analyse what the sensory assessment tells us about the research question.

Sensory scientists always work in groups, called panels, to make sure that no one taster skews the results. A typical panel has 5 to 7 tasters, who train for six to nine months to achieve calibration with the lexicon and with each other before they begin evaluating samples. Sensory lexicons are not unique to coffee. They have existed for many years and exist for many products that are probably familiar (beer, wine, honey, cheese) and some that are not (cat litter!?).

What are you most excited about working on with WCR in the next year?

In March of this year, we hired a new research director, George Kotch. He comes with decades of experience in running highly effective breeding programs for other crops. With George at the helm, we will be shifting to a “demand-led” breeding approach – working to extensively define what qualities and traits matter most to the end users of varieties – farmers and coffee buyers, and then working through a backward design process to target those traits in the development of new varieties. We will be bringing that approach to key countries to help them modernise their breeding programs to be truly responsive to the needs of those using coffee (both in the filed and in roasting drums).

What can us coffee drinkers do to help?

Care about and commend the companies that are doing hard work to support collaborative efforts to make coffee better for farmers and for the future!

You can read more about World Coffee Research on their website here.

Blossom Coffee Roasters is a proud member of WCR’s checkoff program, meaning that for every kilo of coffee we buy we make a small donation towards supporting their pioneering work.

With the dust beginning to settle after a busy first week down here at Blossom, this felt like a good opportunity to clear a little room on the desk, take a quick breather and tell you a little more about how Blossom has transformed from a sketchy vision schemed up over a pint at the Pilcrow pub to a what it is today, something we feel incredibly proud of.

It is fair to say that getting to this point hasn’t been without its struggles (you can’t plan for a global pandemic) but along the way we have been guided and supported by an extraordinarily talented bunch. Their patience, expertise and enthusiasm has kept Blossom on track even on the foggiest of days. But before we introduce you to the creative team behind it all, it’s probably worth setting the scene a little so you know exactly why we were driven to set up a sustainability-focused coffee roastery in first place.

Josh and I have been friends (and very briefly colleagues) since we both returned home to Manchester after working away in different parts of the world. I spent a six year stint down in London getting into the speciality coffee industry, first honing my skills at Prufrock under the ever watchful eyes of Jeremy Challender and Gwilym Davis, before branching out into other areas, including sales and training.

At around the same time, Josh was happily eating and drinking his way around the world before becoming captivated by the cafe culture of New Zealand. This new found love affair would eventually lead to him cancelling his other travel plans in order to immerse himself in the speciality coffee scene there and eventually take on a roasting apprenticeship at Coffee Supreme in Melbourne, Australia. It was during this time that Josh began to think more closely about accessibility in our industry and how speciality coffee’s appeal could be broadened to include those from outside the current niche. It is his belief that in order to have a genuinely positive impact, speciality coffee needs to be opened up to a much larger audience.

On the other side of the world, I had begun participating in and organising annual beach cleans with the lovely folks at Surfers Against Sewage, and in turn had began to unearth some incredible companies popping up that had sustainability as their central message. What had struck me during this time was how many of the like-minded folk I spent my time outside of work with would make ethical and considered decisions about most areas of their lives, buying clothing from brands who champion ethical production and environmentalism for example, but still ended up buying their coffee cheap from a supermarket. There seemed to be a disconnect between enjoying and protecting the natural environment and buying environmentally considered coffee. Inspired by Patagonia and their approach of standing for something much larger than just a clothes brand I began to dream about creating a coffee company that could represent the values I stood for.

On a camping trip last summer, we came to realise that our ideal visions for a roastery were aligned, agreeing that it would have to stand for more than just coffee: a roastery that cares about its impact on people and planet, is driven by becoming more accessible to the wider public and creates a movement that helps to protect speciality coffee for future generations in the face of climate change. A month later at the Pilcrow pub – coincidentally now just a stones through away from our central Manchester location – the idea for Blossom was formed.

In order to make any of this ambition a reality we knew we would have to lean heavily on the experience and expertise of others. On paper we are a small team of two here at Blossom but over the last six months it really has felt like a much bigger collective and collaborative effort, a nice reminder that by working together we can achieve more than we can by going it alone.

‘With Love Project’ – Design/Brand

“We are a creative team that help good people build great brands.”

We first met Chris and Rob, the creative duo behind the ‘With Love Project’, a couple of years ago after we stumbled across their first book ‘The Backbone of Britain’, in which the pair travelled the length of the UK documenting people who produce things with passion and purpose.

Fast forward a year or so and we found ourselves chatting with Chris over a brew at the With Love Pop Up Department Store surround by some of the brands the team have helped to establish over the last few years. As we explored the store and Chris explained the stories behind the projects it quickly surfaced that they had collaborated with brands that had already started to form the inspiration for what we wanted to achieve with Blossom – a company that stood for more than just what they sold, a company with real purpose.

Over the course of the last six months the team at ‘With Love’ have lovingly put together what you see today. Like any good collaboration they’ve supported us but also challenged us. They’ve made our purpose and our resolve stronger, and in doing so helped us feel more sure footed about who we are and what we stand for.

You can read more about them here.

‘Doug Shapley’ – Photography

“I am passionate about using imagery and visual content to communicate a message whether that be about a place, a product or a person”

For us, choosing the right photographer involved a far greater responsibility than simply choosing a particular style. It was important that we found someone who understood and shared our environmental values and who was able to communicate that story in an interesting and engaging way.

Doug has a well established background in conservation and wildlife photography and has written widely about the ability of imagery to inspire others to safeguard nature. We have been totally blown away by his ability to capture often complex narratives in a set of still images and his direction on the aesthetic feel of the brand has been invaluable to keeping Blossom accessible.

You can see more of his work here.

Hannah Valentine – Illustrations

Hannah is responsible for some of the most interesting and eye-catching artwork in the city and we’ve absolutely loved her work since we saw her window campaign for the Patagonia Manchester store.

We asked Hannah to help us bring some additional flourishes to the brand including the semi circles that feature throughout our website and the illustrations for the Environmental Impact Report.

You can see more of Hannah’s work here.